‘Outbreak’ puts the life cycle of an epidemic on display

In 1918, a pandemic of Spanish flu killed as much as 5 percent of the world’s population. A hundred years later, scientists know much more about how to prevent and treat such diseases. But in some ways, the threat of a global outbreak is greater than ever. All it takes is one plane ride for a few localized cases of a disease to become an epidemic.

A new exhibit at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., traces the way infectious diseases still shape our world. The exhibit, called “Outbreak: Epidemics in a Connected World,” is centered around the concept of One Health — the idea that the health of humans, other animals and the environment are all intertwined, so protecting one requires protecting all (SN: 3/31/18, p. 20).

News coverage of disease outbreaks often focuses on the deaths they cause, notes Jonathan Epstein of EcoHealth Alliance, the exhibit’s chief science adviser. One goal of the exhibit, he says, is “to give the public a look at how these things get started.” With that in mind, “Outbreak” highlights a handful of epidemics that have occurred in the last century, using each as a jumping off point to explore different aspects of preventing, tracing, treating and containing infectious diseases.

In addition to zeroing in on epidemics that have made international headlines, including Ebola and SARS, the exhibit features lesser-known diseases. Nipah virus, for instance, has infected people in Bangladesh who have drunk sweet date palm sap contaminated by infected bats. Simple preventive measures like encouraging people not to drink the raw sap or to filter it, so far, have prevented the virus from sparking an epidemic.

“Outbreak” is more focused on text and interactive screens than on artifacts, which makes sense given the microscopic subjects. But the exhibit does draw on the Smithsonian’s extensive collections, showcasing arrays of preserved infectious disease vectors, such as ticks and mosquitoes, as well as bat and macaque specimens. As these display cases explain, monitoring the health of animal populations helps researchers put preventive measures in place before emerging infectious diseases can jump to humans.

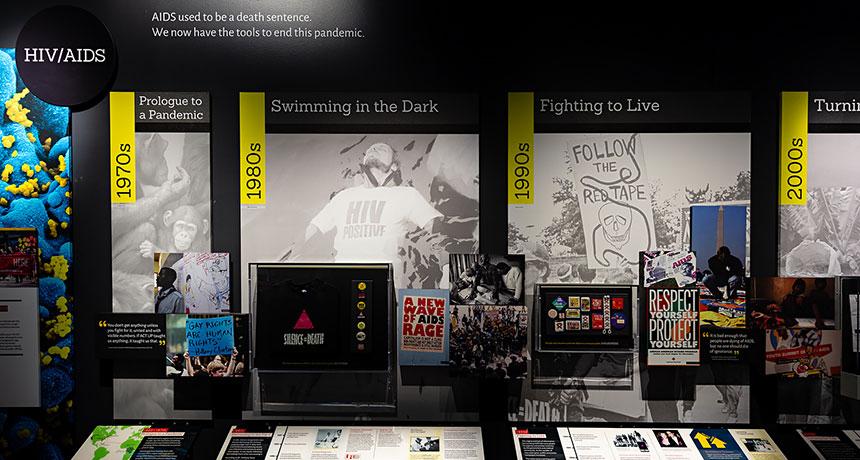

As an entry point for discussing the social side of disease and the stigma that infected people can face, a collection of buttons and signs from AIDS activists recalls the fight for public recognition and government action in the 1980s and ’90s.

The content on display might not be a good fit for very young children, but interactive games and activities throughout increase the exhibit’s overall kid appeal. In one game, played on touch screens, players each pick from a variety of roles — such as epidemiologist, wildlife biologist or community worker — and then cooperate to complete tasks that stem the tide of a fictional outbreak. (It’s a good example of the broader message that stopping infectious diseases requires collaboration from many different kinds of experts.)

In case Washington isn’t on your travel agenda, the Smithsonian is translating the content into multiple languages and sharing it with libraries, community centers and other institutions around the world to help them create their own pared-down versions of the exhibit.