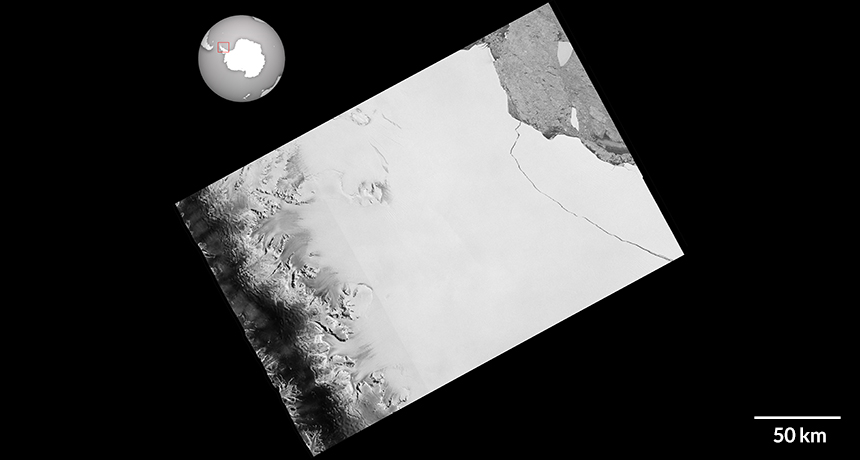

Delaware-sized iceberg breaks off Antarctic ice shelf

With a final rip, an iceberg roughly the size of Delaware has broken off Antarctica’s Larsen C ice shelf. Anticipated for weeks, the fracture is one of the largest calving events ever recorded.

On July 12, satellite images confirmed a nearly 5,800-square-kilometer, 1-trillion-metric-ton chunk of ice, equivalent to 12 percent of Larsen C’s total area, split from the ice shelf. “[We] have been surprised how long it took for the rift to break through the final few kilometers of ice,” Adrian Luckman, a glaciologist at Swansea University in Wales, said in a blogpost for Project MIDAS, which has been tracking the effects of a warming climate on the ice shelf. Now the focus will shift to the stability of the remaining ice shelf and the fate of the giant iceberg.

Scientists had been monitoring Larsen C since 2014, when they noticed that a crack in the ice shelf had grown roughly 20 kilometers in less than nine months (SN: 7/25/15, p. 8). After a relative lull in 2015, the crack grew another 40 kilometers in 2016 and then 10 more in the first half of January 2017, bringing its total length to 175 kilometers. At that point, its tip was 20 kilometers from the Weddell Sea.

The crack grew another 17 kilometers between May 25 and May 31 — at times traveling parallel to the edge and ultimately putting it within 13 kilometers of the ice front. Then, in late June, the outer part of the ice shelf picked up speed, putting new pressure on the crack and the entire shelf. “It won’t be long now,” Project Midas tweeted June 30. Added Luckman, also in a tweet: “The remaining ice is strained near to breaking point.”

Yet the vigil lasted nearly two more weeks. By July 6, the crack had come within 5 kilometers of the edge of the ice. Then, sometime between July 10 and July 12, it finally reached the water, allowing the huge hunk of ice to splinter off into the sea.

The ice loss dramatically alters the landscape of Larsen C, Luckman notes. “Maps will need to be redrawn.” And that could be the least of the trouble ahead, says Adam Booth, a geophysicist at the University of Leeds in England also with Project MIDAS. “The calving event is significant because it is likely a precursor to something much bigger, potentially the collapse of the whole Larsen C ice shelf,” Booth says. The same thing happened to the neighboring Larsen B ice shelf in 2002, after it calved a Rhode Island-sized iceberg (SN: 3/30/02, p. 197).

“Glaciologists are keen to see how Larsen C will react,” says Luckman.

A complete collapse of Larsen C could have implications for sea level rise. Antarctica’s ice shelves act as buttresses, helping to slow the flow of the continent’s ice into the ocean. Since these shelves float on the water, calving icebergs don’t directly raise sea level. But calving or the collapse of an ice shelf allows glaciers and ice streams further inland to flow into the ocean, which can contribute to sea level rise.

Calving of icebergs is common, and over several decades, the shelves usually recover to their original size. But in the last two decades, ice shelves have instead continued to lose ice until collapsing, probably as a result of rising temperatures due to climate change, researchers suspect. In 2014, researchers concluded the collapse of Larsen B was the result of warming (SN: 10/18/14, p. 9).

Some computer simulations suggest Larsen C could suffer the same fate, possibly within a few years to decades, Luckman says. Still, the calving event that feeds a potential collapse may be hard to pin on climate change. “Not all ice-related stories have a clear global warming origin,” Luckman notes. Larsen C’s calving, he says, “may simply be a natural event that would have happened regardless of human activity.”

Not everyone is convinced that Larsen C will fall apart completely. Researchers from Europe predict major changes to the shelf would happen only if it loses 55 percent of its ice. At that point, a significant amount of ice could ooze from glaciers into the ocean. Still, understanding what allowed the recent rift to grow and calve will “give us insight regarding other fractures or rifts on the shelf,” says geoscientist Dan McGrath of Colorado State University in Fort Collins. While McGrath says a collapse is “very unlikely,” he adds that “these other dormant rifts are in locations where if they reinitiated, the subsequent calving event would be worrisome for the shelf’s stability.”

Discrepancies in the predictions of Larsen C’s fate raise an important point, says Richard Alley, a geologist at Penn State. Researchers don’t understand ice shelf calving and collapsing enough predict how any one individual ice shelf will behave after a break.

“The Larsen C ice shelf is, of course, just one small part of Antarctica,” Booth says. “What is worrying is that we’re seeing trends in several ice shelves that tend towards decreasing stability. Should they continue along these trends, we could be seeing the start of increased mass loss from the Antarctic continent.”