Xiconomics in Practice: Under Xi's leadership, China moves swiftly to help private sector tackle challenges, achieve sound devt

Editor's Note:

Since 2012, China has witnessed an extraordinary economic transition, with historic achievements in all aspects of the economy from its size to quality. Such an unparalleled feat does not just happen, especially during a tumultuous period in the global geo-economic landscape and a tough phase in China's economic transformation and upgrading process. It was Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era that guided the country in overcoming various risks and challenges, and in keeping the China economic miracle alive.

As China embarked on the quest to become a great modern socialist country amid global changes unseen in a century, Xi's economic thought has been and will continue to be the guiding principle for development in China for years to come, and have great significance for the world. What is Xi's economic thought? What does it mean for China and the world? To answer these questions, the Global Times has launched this special coverage on Xi's major economic speeches and policies, and how they are put into practice to boost development in China and around the world.

In China's economic policymaking, policymakers and economists often use a rather apt term to describe the integral role the private sector plays in the country's social and economic development: "56789." This refers to private firms' contribution of more than 50 percent to national tax revenue, more than 60 percent to the national GDP, more than 70 percent to technological innovation achievements, more than 80 percent to urban employment, and 90 percent to the total number of enterprises in China.

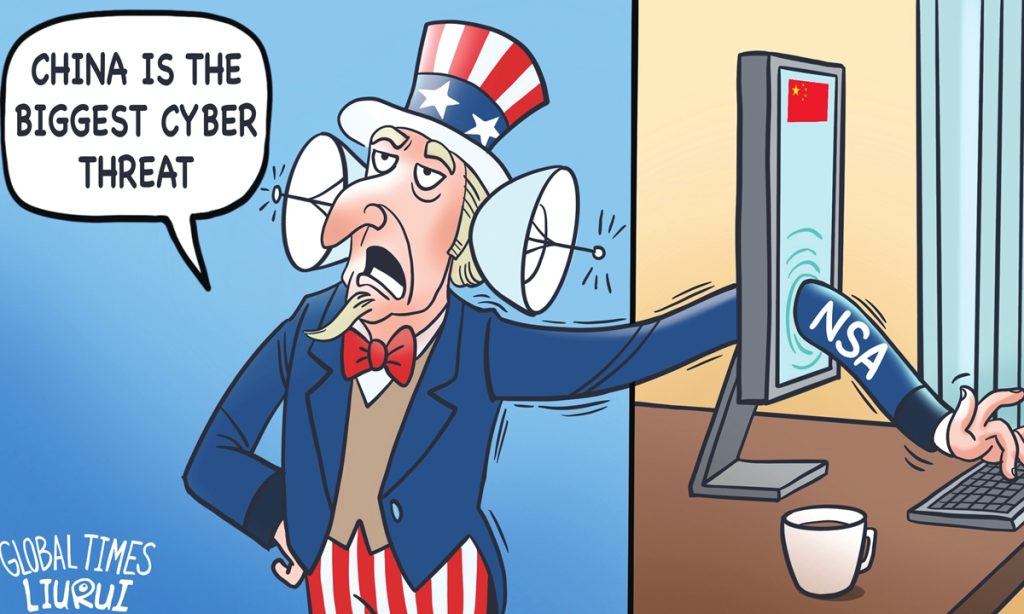

More than describing private firms' enormous contributions to China's overall development, the phrase also lays bare the weight of the private firms in China's economic policymaking. And yet, whenever private firms, or the Chinese economy, encounter challenges, some at home and abroad levy obsolete claims against China's policy for the private sector. Some foreign media sources describe normal industrial regulation as "crackdowns," while others seek to paint a dire outlook for Chinese private firms.

Evidently, this has, to some extent, led to negative sentiment among some private firms, as private fixed-asset investment shrank by 0.2 percent year-on-year in the first half of 2023, with a 0.6-percent contraction in June alone, according to official data.

This further fueled pessimism toward Chinese private firms and even the Chinese economy as a whole. The IMF said last month that China's economy was slowing due to weaker private investment.

Are Chinese policymakers paying less attention to private firms, or engaging in "arbitrary crackdowns?" Are private firms facing an increasingly grim outlook in China?

After conducting interviews with more than a dozen Chinese private firms, entrepreneurs, and experts, the Global Times found that, while challenges remain, the private sector remains overwhelmingly confident in operation and future growth, pointing to increasing support from policymakers and China's overall economic prospects. Personal care and support for the private sector from President Xi Jinping have become a source of confidence for the country's vast private sector.

Support from top leader

Xi, also general secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee, has, at important meetings and inspection tours around the country, commended the crucial contributions of the private sector to China's social and economic development and voiced unwavering support for the high-quality development of private firms.

"The CPC Central Committee has always considered private enterprises and private entrepreneurs as being in our ranks," Xi said in March, while visiting national political advisors from the China National Democratic Construction Association and the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, who were in attendance at the first session of the 14th National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC).

Wang Yu, a member of the National Committee of the CPPCC and chairman of Spring Airlines, was among the national political advisors who were in attendance when Xi visited. "I am very touched!" Wang said at the time, noting that Xi's remarks helped "eliminate any worry among the vast number of private entrepreneurs and set our minds at ease, and greatly boosted our confidence in continuing to overcome difficulties."

In a recent interview, Wang said that a slew of recent policy measures for private firms further demonstrated Xi and the CPC Central Committee's unwavering support for the private sector. "Although China's economy is stabilizing and improving, the external situation is complicated and severe, and it still faces the huge test of 'triple pressures.' Private enterprises, especially small and medium-sized ones, have been more affected and impacted. At such a time of difficulty and confusion, the Party and the government have provided firm support and clear guidance," Wang told the Global Times.

On July 19, the CPC Central Committee and the State Council released a guideline on boosting the growth of the private economy, vowing to improve the business environment, enhance policy support, and strengthen the legal guarantee for the development of the private economy. Containing 31 measures, the guideline addressed major challenges faced by the private sector.

On July 24, Xi presided over a meeting of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee to analyze economic situation and make arrangements for work in the second half of the year. The meeting called for policies and measures to promote private investment and provide private enterprises with an enabling environment. It also stressed upholding the principle of unswerving consolidation and development of the public sector and unswerving encouragement, support, and guidance of the development of the private sector, or "the two unwaverings," which is also a key aspect of Xi's economic thought.

"A series of recent weighty documents will not only strengthen the importance attached to and support for the private economy, but will also provide a stronger policy guarantee for the development of the private economy in the new era through a series of new measures that are normalized and based on the rule of law, and will further stabilize expectations and boost confidence," Li Jin, chief researcher at the China Enterprise Research Institute in Beijing, told the Global Times.

Efforts to tackle challenges

Highlighting the ultra-efficiency of policymaking and execution unique to China's system, and following the remarks and policy guidelines from the top leadership, various ministries have, in recent days, issued a slew of measures to help private firms tackle major challenges and ensure steady, sound development of the private economy.

Last week, eight Chinese ministries issued 28 measures to support the private sector, vowing to provide fair access for private firms to participate in major national projects and technological undertakings, increasing financial and land support, and strengthening the legal protection of the private firms.

On Sunday, the State Taxation Administration announced 28 measures to facilitate tax payments and promote the development of the private sector.

The measures have been well received by private entrepreneurs around the country, who described them as "timely rain" that will help them address major challenges they are facing in a targeted manner.

Chen Xu, chairman of the SENKEN Group, a police appliances manufacturing company in Wenzhou, East China's Zhejiang Province, said that the company faces relatively big burdens in areas such as tax, research and development (R&D) investment, and rising labor costs, and recently implemented measures address such challenges.

"In particular, measures aimed at providing fair market access for private firms is very helpful for us," Chen told the Global Times, adding that other measures to help protect intellectual property are also very important to the firm, as it spends more than 30 million yuan on R&D each year.

Wang Shaoshao, founder of Ouhua, a small business in Zhejiang that focuses on flowers and related cultural products, said that recent policy measures supporting the land use of private firms greatly help the company, as it seeks to rent land for business activities.

Cai Qinliang, head of a company specializing in Christmas decorations manufacture in Yiwu, Zhejiang, said that exports orders are gradually returning to pre-pandemic levels and other challenges such as surging shipping costs are easing thanks to increased policy support.

"From production to shipment and customs, the policies issued by the government are very conducive to the development of the enterprise, which can ensure that we can clear customs and ship out goods as soon as possible," Cai told the Global Times, noting that recent measures aimed at cutting processing time for tax rebates to less than six working days and extending loans for small businesses, in particular, will help ease firms' financial burdens.

Zhejiang is one of the largest private business hubs in China, with the private sector enterprises accounting for over 70 percent of its economic activity. Zhejiang plays a crucial role in leading national efforts to boost the confidence of private firms, analysts said.

Upbeat on future prospect

Contrary to the rather dark picture painted by certain foreign media outlets, private entrepreneurs expressed confidence in their future outlook, thanks to firm support from the top leadership and concrete measures that help address challenges they face. Moreover, there are emerging signs that point to the resilience of the private sector in face of challenges.

In the first seven months of 2023, exports and imports by the private companies totaled 12.46 trillion yuan, up 6.7 percent year-on-year, becoming a bright spot in China's overall trade in the face of downward pressure, official data showed on Tuesday. This growth rate is significantly higher than the 0.4 percent year-on-year growth rate in China's foreign trade registered for the same period in 2022. Notably, the share of private firms' exports and imports in the country's total foreign trade rose to 52.9 percent.

"In fact, the production and order situation of our company in 2022 has recovered to about 90 percent of the pre-pandemic level, and it is still gradually improving this year and expected to basically return to the pre-pandemic level," Cai with the Christmas decorations manufacturing firm said, also adding, "with strong policy support, we are quite confident in the future."

Chen, chairman of SENKEN, said that despite challenges, the company is moving along steadily with its five-year plan for a listing on the stock market by 2024. It is also actively expanding its overseas market, even after having exported products to more than 60 countries and regions. "The hope is that our brand can be competitive and influential overseas," he said.

And for the private sector, the country's firm support is for long term, rather than a short-term boost measure. "The '56789' feature of the private economy has not changed, and private firms are inseparable from the Chinese economy," Li said, adding that the private sector plays an increasingly crucial role in the country's pursuit of high-quality development and ultimate Chinese modernization.

More forms of long-term policy support are expected for private firms, as Xi put it in March, to boost their confidence and unburden them of their worries, so that they can ambitiously pursue development.