Many Antarctic glaciers are hemorrhaging ice. This one is healing its cracks

This environment is “really at the edge” between melting and freezing, says planetary scientist Justin Lawrence. The delicate balance between these two processes is shaping the ice into those strange textures — similar to the way that minerals dissolve and recrystallize to form the beautiful shapes inside limestone caverns.

The result, at Kamb Ice Stream, is that massive cracks in the underside of the ice appear to be freezing back together as the beach ball–sized globes fill in the crevasses from above, Lawrence and colleagues report March 2 in Nature Geoscience.

This refreezing differs from what’s happening at Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier. There, scientists recently reported that these cracks, known as basal crevasses, are instead sites of rapid melting (SN: 2/15/23).

Understanding what is happening at Kamb will help scientists predict how large parts of the Antarctic coastline that are not currently vulnerable might respond as the world continues to warm due to human-caused climate change. Here’s what’s different about Kamb.

Supercold water underlies the ice at Kamb, slowing melting

In December 2019, two teams of researchers from New Zealand and the United States visited the Kamb Ice Stream — a type of glacier that consists of a channel of faster-moving ice surrounded by slower ice.

Kamb, like much of the rest of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, rests on a bed that is hundreds of meters below sea level. The New Zealand team used hot water to melt a narrow hole through the ice, just downstream of the “grounding zone,” where the glacier lifts off its muddy bed and floats on the ocean.

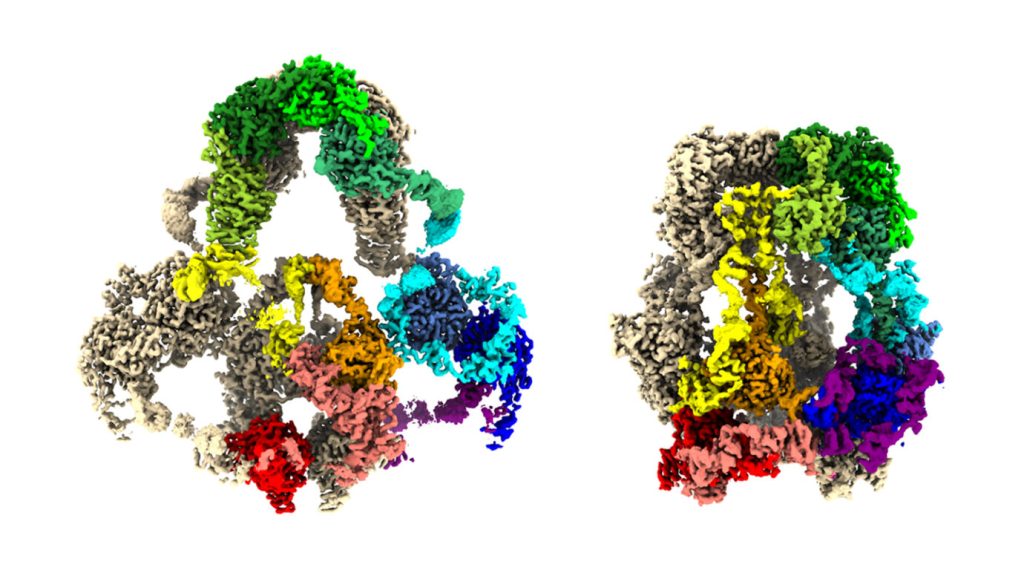

The U.S. team then lowered a remote-operated vehicle called Icefin down through 580 meters of ice and into the seawater below. The researchers piloted Icefin as far as a kilometer from the borehole, navigating by video transmitted up through a cable. At the time of the expedition, the team operating Icefin was affiliated with Georgia Tech in Atlanta, but has since moved to Cornell University, except for Lawrence. He now works for Honeybee Robotics, a private company in Altadena, Calif.

Icefin found that much of the seawater beneath Kamb is about 0.3 degrees Celsius above freezing. But directly below the ice sits a colder layer, a mixture of seawater and glacial meltwater just 0.02 to 0.08 degrees C above freezing. Based on these measurements, Lawrence and his colleagues estimate that the exposed underside of Kamb is melting about 26 centimeters per year.

In contrast, recent measurements at the increasingly unstable Thwaites Glacier, about 1,400 kilometers to the northeast, found the seawater at the glacier’s grounding zone 1 to 2 degrees C warmer than at Kamb — and the ice melting 5 to 40 meters per year.

The new finding at Kamb makes sense, says New Zealand team member Christina Hulbe, of the University of Otago, because the seabed at Kamb is relatively shallow. So it is not exposed to the deep, warm ocean currents that are hitting Thwaites.

Much of Antarctica is fringed by cold ocean environments similar to Kamb, she says. “So just understanding that system is important.”

Greenish globs of refrozen ice fill cracks at Kamb

As Icefin glided along, its sonars detected massive basal crevasses up to 55 meters across in the ice above. These cracks probably formed as the floating part of the glacier, the ice shelf, flexes up and down with ocean tides.

Lawrence and his colleagues guided the ROV into one of these cracks, and found its white, icy sidewalls carved into narrow vertical grooves. Icefin ascended 40 meters up, until the grooves suddenly vanished — replaced by a jumble of ice globes, which seemed to fill the upper half of the crevasse.

The globes were greenish — a hue often seen in winter ice that forms on the surface of the ocean. This color makes Lawrence and his colleagues think that the globes form from the ultracold mixture of seawater and meltwater that circulates up into a crack and refreezes, gradually filling in the crack, from the top down, over many decades. They think that this is happening in all of the crevasses they observed. “These crevasses are effectively healing themselves,” he says.

This refreezing process might also explain the strange vertical grooves in the walls of the crevasse, Lawrence speculates. As the water freezes, salt is pushed out of the newly forming ice crystals, creating tiny pockets of highly concentrated brine. That dense brine streams down the walls, melting grooves into the ice — similar to the way that salt causes ice to melt when it’s sprinkled onto a sidewalk in the wintertime.

To observe the crevasses refreezing under Kamb “is pretty exceptional,” says Ginny Catania, a glaciologist at the University of Texas at Austin who was not part of the project. Those cracks “can propagate all the way to the surface and cause calving” of icebergs, she says, which can shrink the ice shelf if it happens too quickly, destabilizing the glacier and raising sea level.

But if the crevasses can actually heal, this could make these ice shelves more resistant to calving — and more stable — than scientists realized, at least as long as the ice continues to be bathed in cold water on the underside.

A string of instruments installed in the hole continued to measure the temperature and salinity of the water beneath the ice — transmitting that data up a cable to the ice’s surface, and back home via satellite until the batteries ran out two years later. Those data show that conditions down below remained cool and comfortable for Kamb.