Kepler telescope doubles its count of known exoplanets

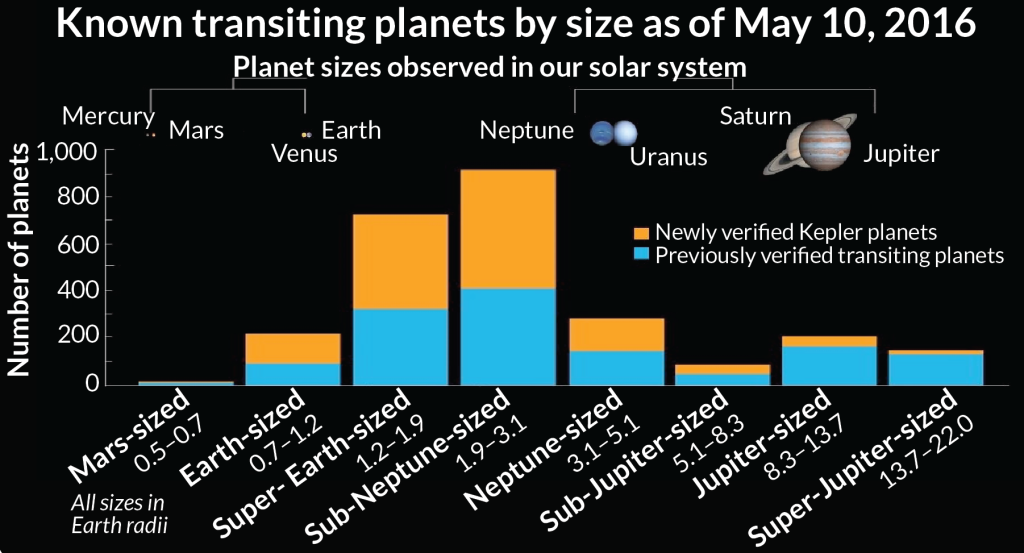

The galaxy is starting to feel a little crowded. Over 1,000 planets have just been added to the roster of worlds known to orbit other stars in the Milky Way, researchers announced May 10 at a news briefing. This is the largest number of exoplanets announced at once.

Most of the 1,284 worlds are larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune. Many of those are probably big balls of gas. But over 100 of the new discoveries are smaller than 1.2 times the diameter of Earth. “Those are almost certainly rocky in nature,” said Timothy Morton, an astrophysicist at Princeton University. Nine planets also lie within the habitable zone, the distance from the star where liquid water could conceivably collect on the surface of the planet. Morton and colleagues detail their findings in the May 10 Astrophysical Journal.

This announcement roughly doubles the number of planets discovered by NASA’s planet-hunting workhorse, the Kepler space telescope, which has now found 2,325 exoplanets. Kepler spent nearly four years staring at about 150,000 stars in the constellations Cygnus and Lyra, watching for subtle dips in starlight as planets crossed in front of their suns. While Kepler has since moved on to other investigations (SN: 6/28/14, p. 7), this latest haul comes from those first four years of observing.

The planet bonanza comes courtesy of a new statistical calculation that allows researchers to feel confident that a detection is a real world. Impostors such as companion stars can mimic the signal from a planet. Traditionally, each planet candidate must be followed up with intensive observations from ground-based telescopes. But with over 4,000 candidates in the queue, confirming each one would take a long time. The calculation takes into account the details of how a passing planet should dim and brighten the starlight along with how common impostors should be and provides a reliability score for each candidate. Planets in this study are those whose score is greater than 99 percent.

Techniques such as these should help confirm planets detected by upcoming missions such as the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, scheduled to launch in late 2017. Some of those planets found by TESS will in turn come under the gaze of the James Webb Space Telescope, which will launch in 2018 and investigate their atmospheres (SN: 4/30/16, p. 32).

Editor’s Note: This story was updated May 17, 2016, to correct the key in the graphic to indicate that previously detected planets include all transiting planets discovered, not just the ones found by Kepler.