Nuclear blasts, other human activity signal new epoch, group argues

Humankind’s bombs, plastics, chickens and more have altered the planet enough to usher in a new chapter in Earth’s geologic history. That’s the majority opinion of a group of 35 experts tasked with evaluating whether the current human-dominated time span, unofficially dubbed the Anthropocene, deserves a formal place in Earth’s geologic timeline alongside the Eocene and the Pliocene.

In a controversial move, the Anthropocene Working Group has declared that the Anthropocene warrants being a full-blown epoch (not a lesser age), with its start pegged to the post–World War II economic boom and nuclear weapons tests of the late 1940s and early 1950s. The group made these provisional recommendations August 29 at the International Geological Congress in Cape Town, South Africa.

If eventually approved by the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) — the gatekeepers of geologic time — and the Executive Committee of the International Union of Geological Sciences, the Anthropocene would usurp the current Holocene Epoch, which has reigned since the end of the last glacial period around 11,700 years ago. The Holocene would become the shortest completed epoch in history, just thousandths the length of the next shortest epoch.

“We’ve left an indelible mark on the Earth,” says Jan Zalasiewicz, a geologist at the University of Leicester in England and convener of the working group. “We now cannot go back to anything that’s ostensibly the same as the Holocene.”

Not all scientists are onboard with the plan. Critics say it’s grounded in politics and pop culture, not science, and that not enough time has passed to put just decades-old changes in context. Any proposal advocating for the Anthropocene will face strong skepticism, says Whitney Autin, a sedimentary geologist at the State University of New York at Brockport. “The idea of amending geologic time carries the same weight as eliminating an amendment to the U.S. Constitution,” he says.

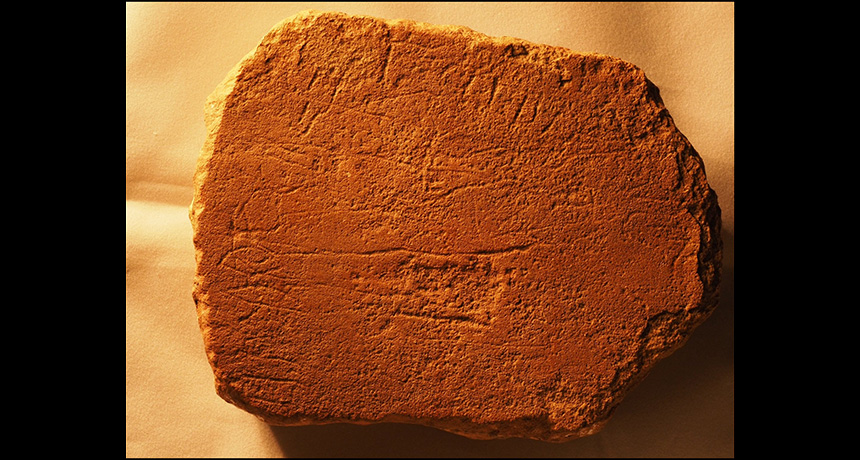

To build its case for the new epoch, the working group will spend the next two to three years scouring natural records, such as rocks, mud and tree rings, for evidence that humankind’s impacts have brought about a distinct new phase in the stratigraphic record. The group will then submit a formal proposal for approval.

“We’re leaving physical signals in sediments, in corals, in trees that are going to be long lasting if not permanent,” says Colin Waters, a geologist at the British Geological Survey in Keyworth and a member of the working group. “It’s not just history, it’s geology as well.” And those geologic changes merit official recognition as a new epoch, Waters says.

The goal of the geologic time scale is to label and formalize discrete phases in Earth’s stratigraphic record as a tool for geologists and other scientists. This time scale allows scientists to easily identify, describe and discuss rocks of similar age across the planet.

The term “Anthropocene” has risen in popularity among scientists and the general public in recent years, driven in part by its use in a 2002 article by atmospheric chemist and Nobel laureate Paul Crutzen. The article argued that humans’ exploitation of natural resources has reshaped the planet enough to bring about a new epoch.

While “Anthropocene” now appears in the titles of papers, conference talks and books about everything from climate change to philosophy, those who embrace the term nonetheless disagree on its definition. Some researchers pin the start of the epoch to when humans first started converting forests to farmland thousands of years ago, while others, such as Crutzen, use the start of the Industrial Revolution or the recent acceleration in fossil fuel burning.

The Anthropocene Working Group was convened by the ICS in 2009 to sort out the definition of the Anthropocene and assess whether the time interval should be formally added to the geologic time scale. Among its 35 members, the working group contains an international mix of geologists, climate scientists, archaeologists and other experts.

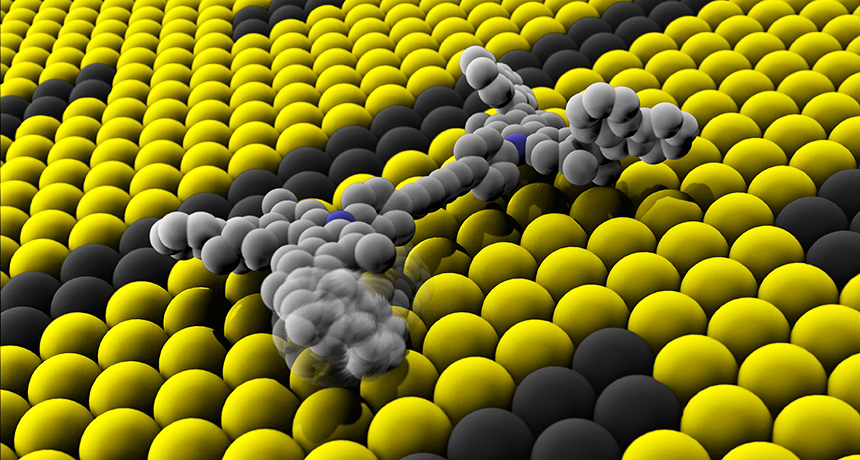

In January, members of the working group published a review of evidence for the Anthropocene in Science. Pro-Anthropocene arguments come from multiple areas of science, from biology to climate to chemistry, the researchers reported. For instance, humans have introduced species such as the domestic chicken worldwide and driven many others to extinction (SN Online: 8/26/15). Emissions from human activities such as fossil fuel burning have altered Earth’s climate (SN: 4/16/16, p. 22). Manufactured materials such as plastics, aluminum and concrete will remain embedded in the ground as “technofossils.” Fallout from nuclear weapons tests has left a radioactive mark in soil, marine sediments and even ice. These human impacts make the Anthropocene distinct in the stratigraphic record from the Holocene, the researchers concluded.

For the Anthropocene to become official, the working group will have to establish a starting point for the proposed epoch. That can be accomplished by picking a nice round number — the Hadean-Archean switchover is an even 4 billion years ago, for instance — or by linking the starting point to a physical marker in the global sedimentary record, an approach now favored by ICS.

The marker for the start of the Holocene, for instance, is linked to chemical and physical changes in the Greenland ice sheet caused by the warming that brought Earth out of its last bout of glacial growth. Such markers — also called “golden spikes,” similar to the ceremonial spike that marked the union of the first U.S. transcontinental railroad — are chosen for being ubiquitous and consistent throughout the world.

Golden spikes are not necessarily important or even relevant to the differences that distinguish geologic time frames, says Stan Finney, a geologist at California State University, Long Beach, and former chair of the ICS. For instance, the Thanetian Age — a 3.2-million-year stretch during the Paleocene Epoch — is marked by just one of many reversals in Earth’s magnetic field.

While a golden spike’s geologic signal may be global, the official physical spike itself is literally a single point in the stratigraphic record somewhere on Earth. (A single point avoids the problem of using multiple points that could end up having different ages, muddling the time boundary.) The golden spike for the Holocene is inside an ice core collected from Greenland and kept chilled in a freezer at the University of Copenhagen.

The need for a golden spike shaped the working group’s Anthropocene proposal, Zalasiewicz says. While phases in human history such as early agriculture and the Industrial Revolution have had profound impacts on the planet, they didn’t have a simultaneous worldwide effect that could be used to mark the start of the new epoch. Had a major volcanic eruption spewed a distinctive layer of ash across the globe near the start of the Industrial Revolution, “it would have been a pretty good candidate,” Zalasiewicz says. Even though the eruption would have had nothing to do with human activity, the ash would have been a ubiquitous and easily identifiable marker for geologists.

Radioactive carbon and plutonium blasted from the ramp up in atmospheric nuclear tests during the 1950s is another story. And the timing is so recent that it opens up many new places to hunt for the proposed epoch’s golden spike, including in living organisms such as trees and corals. “We’re a bit like confused kids wandering around an enormous sweetshop wondering how we’re going to choose,” Zalasiewicz says.

Even if the group finds a golden spike, its proposal will face criticism from scientists who contend that the Anthropocene doesn’t warrant its own epoch. Radioactive fallout “is a widespread marker that qualifies for the rules that they need to follow to make a recommendation,” says William Ruddiman, a professor emeritus at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, “but that doesn’t mean that it’s right, or that it makes sense.”

Not enough time has passed since the proposed start date of the Anthropocene to have enough perspective to put the observed changes in the sedimentary record in proper context, Autin says. “A lot of stratigraphers would say that maybe in thousands or millions of years there will be a distinctive demarcation in the rock record at this point in time, but right now it’s a proposal that’s premature.”

Placing the boundary so recently is “dubious, to say the least,” agrees Mike Walker, a professor emeritus at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David who helped establish the golden spike that represents the start of the Holocene. Divisions of geologic time “should have a utility for geoscientists, archaeologists, anthropologists, et cetera,” he says. “I see little of value to the wider science community in an epoch boundary at A.D. 1950.”

The formalization of the Anthropocene is not just scientifically motivated, but also driven by a desire to highlight humankind’s impact on the environment, suggests Lucy Edwards, a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Reston, Va. “It’s a meme,” she says. “The thinking is that if you have a concept and you give it a new word, it carries more weight.”

The motivation behind the newly announced proposal isn’t overly focused on humankind being to blame for recent changes, Zalasiewicz responds. “If we had all the same changes, but caused by something else, like volcanoes or a meteorite or my cat, then it would be just as significant.”

More time isn’t needed to recognize that modern sediments are unique, he adds. After all, he says, if humans had been around 50 years after the environmental catastrophe that wiped out the dinosaurs about 66 million years ago, they would have clearly seen that Earth’s environment and ecology had permanently changed.