Gene editing of human embryos gets rid of a mutation that causes heart failure

For the first time in the United States, researchers have used gene editing to repair a mutation in human embryos.

Molecular scissors known as CRISPR/Cas9 corrected a gene defect that can lead to heart failure. The gene editor fixed the mutation in about 72 percent of tested embryos, researchers report August 2 in Nature. That repair rate is much higher than expected. Work with skin cells reprogrammed to mimic embryos had suggested the mutation would be repaired in fewer than 30 percent of cells.

In addition, the researchers discovered a technical advance that may limit the production of patchwork embryos that aren’t fully edited. That’s important if CRISPR/Cas9 will ever be used to prevent genetic diseases, says study coauthor Shoukhrat Mitalipov, a reproductive and developmental biologist at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. If even one cell in an early embryo is unedited, “that’s going to screw up the whole process,” says Mitalipov. He worked with colleagues in Oregon, California, Korea and China to develop the embryo-editing methods.

Researchers in other countries have edited human embryos to learn more about early human development or to answer other basic research questions (SN: 4/15/17, p. 16). But Mitalipov and colleagues explicitly conducted the experiments to improve the safety and efficiency of gene editing for eventual clinical trials, which would involve implanting edited embryos into women’s uteruses to establish pregnancy.

In the United States, such clinical trials are effectively banned by a rule that prevents the Food and Drug Administration from reviewing applications for any procedure that would introduce heritable changes in human embryos. Such tinkering with embryo DNA, called germline editing, is controversial because of fears that the technology will be used to create so-called designer babies.

“This paper is not announcing the dawn of the designer baby era,” says R. Alta Charo, a lawyer and bioethicist at the University of Wisconsin Law School in Madison. The researchers have not attempted to add any new genes or change traits, only to correct a disease-causing version of a gene.

In the study, sperm from a man who carries a mutation in the MYBPC3 gene was injected into eggs from women with healthy copies of that gene. Carrying just one mutant copy of the gene causes an inherited heart problem called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (SN: 9/17/16, p. 8). That condition, which strikes about one in every 500 people worldwide, can cause sudden heart failure. Mutations in the MYBPC3 gene are responsible for about 40 percent of cases. Doctors can treat symptoms of the condition, but there is no cure.

Along with the man’s sperm, researchers injected into the egg the DNA-cutting enzyme Cas9 and a piece of RNA to direct the enzyme to snip the mutant copy of the gene. Another piece of DNA was also injected into the egg. That hunk of DNA was supposed to be a template that the fertilized egg could use to repair the breach made by Cas9. Instead, embryos used the mother’s healthy copy of the gene to repair the cut.

Embryos’ self-healing DNA came as a surprise, because gene editing in other types of cells usually requires an external template, Mitalipov says. The discovery could mean that it will be difficult for researchers to fix mutations in embryos if neither parent has a healthy copy of the gene. But the finding could be good news for those concerned about designer babies, because embryos may reject attempts to add new traits.

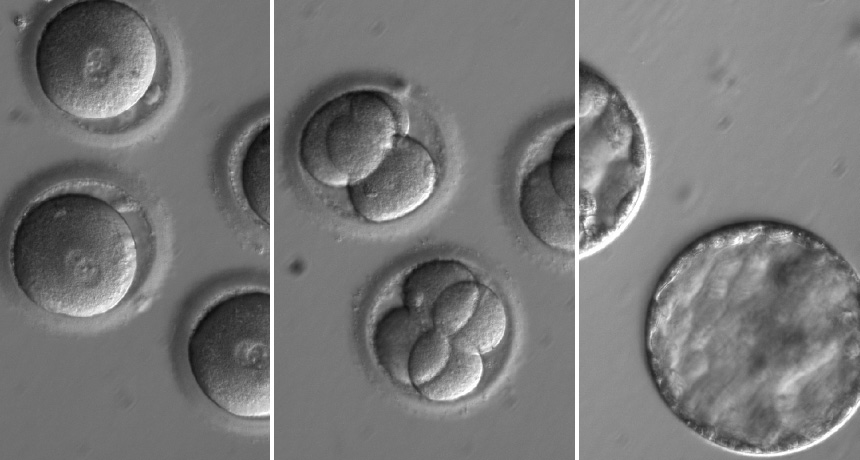

Timing the addition of CRISPR/Cas9 is important, the researchers also discovered. In their first experiments, the team added the gene editor a day after fertilizing the eggs. Of 54 injected embryos, 13 were patchwork, or mosaic, embryos with some repaired and some unrepaired cells. Such mosaic embryos probably arise when the fertilized egg copies its DNA before researchers add Cas9, Mitalipov says.

Injecting Cas9 along with the sperm — before an egg had a chance to replicate its DNA — produced only one patchwork embryo. That embryo had repaired the mutation in all its cells, but some cells used the mother’s DNA for repair while others used the template supplied by the researchers.

None of the tested embryos showed any signs that Cas9 was cutting where it shouldn’t be. “Off-target” cutting has been a safety concern with the gene editor because of the possibility of creating new DNA errors.

The study makes progress toward using gene editing to prevent genetic diseases, but there’s still has a long way to go before clinical testing can begin, says Janet Rossant, a developmental biologist at the Hospital for Sick Children and the University of Toronto. “We need to be sure this can be done reproducibly and effectively.”