Playing ‘a-thief-crying-stop-thief’ trick, US only wants ‘permanent cyber hegemony’

China's Ministry of State Security (MSS) exposed on Wednesday the key despicable methods used by US intelligence agencies in cyber espionage and theft. It also pointed out that the US' infiltration of Huawei headquarters' servers can be traced back to 2009. Despite this, Washington has been attacking Huawei and falsely claiming that Huawei poses a threat to US "national security." Such behavior, characterized by "thief crying stop thief," is a typical American hegemonic behavior.

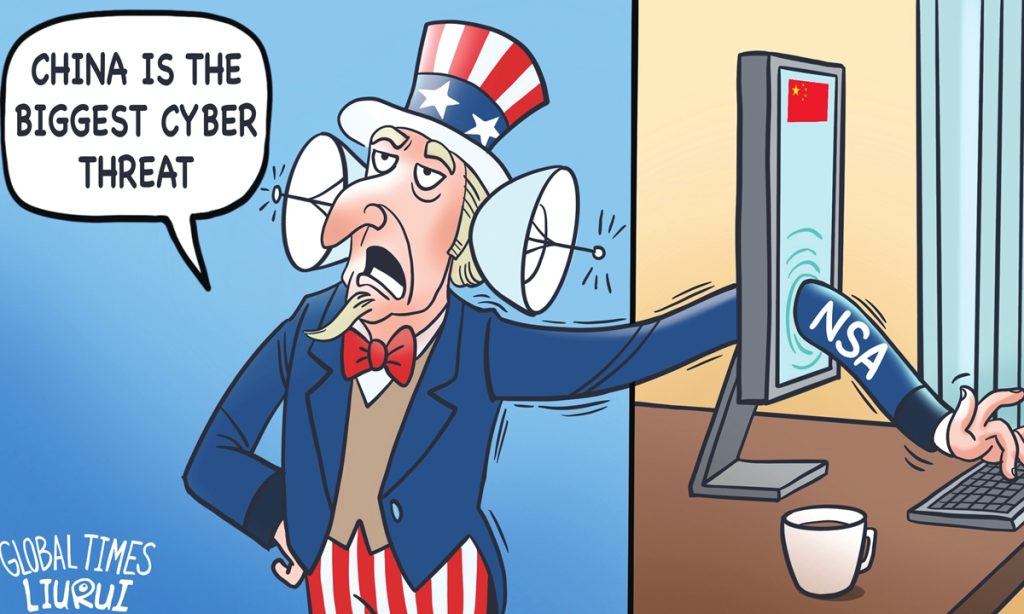

The US has a notorious track record in the field of cybersecurity. According to MSS, the US intelligence agencies, with their powerful arsenal of cyberattack weapons, have been monitoring, stealing secrets, and launching cyberattacks on multiple countries, including China. The US government, citing national security reasons, forcefully implanted backdoors into the devices, software, and applications of relevant technology companies through acts such as the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. By using methods like embedded code and vulnerability attacks, the US achieved global data monitoring and theft, leveraging the influence of global technology companies. But even in this situation, FBI Director Chris Wray shamelessly claimed on Monday that Beijing has a cyber espionage program so vast that it is bigger than all of its major competitors combined. The US, relying on the trick of a thief crying stop thief, attempts to distort the truth, confuse the public, and portray itself as a "victim of cyberattacks." Ultimately, the US aims to smear and suppress whoever it deems as opponents and establish permanent cyber hegemony.

In the process of suppressing and sanctioning Chinese tech companies, the US most frequently uses the excuse of protecting "national security." However, the reality is: It is the US that began to invade Huawei headquarters' servers and carry out continuous monitoring back to 2009. Washington, on one hand, has endangered China's national security by hacking Chinese tech companies, on the other, it has repeatedly suppressed Huawei by restricting chip exports under the pretext of "national security."

Not only does the US exclude various products from Huawei, including telecommunications equipment, but it also requires its allies to exclude Huawei equipment from their 5G network construction. It claims that Huawei equipment may threaten the network security of these countries, particularly in terms of military communication security. The world is witnessing unprecedented technological injustice as the US mobilizes its allied countries to attempt to "strangle" Chinese high-tech company Huawei. It now turns out that Huawei is the victim of US hacking.

The establishment of a cyber arsenal by the US reflects a very important security concept. It is that in the most essential elements of national power, the US must be in an absolute dominant position and must be in a position that no other country can match. This applies to the economic aspect, and it also applies to the cyber field. This is an inherent behavioral pattern for the US.

Facing such a situation, what should China do? One approach is to strengthen its own capacity building in the cyber security field, and it needs to accelerate development as much as possible. The other is to expose to the maximum extent the destructive actions of the US in this field toward the world, the global community, China, US allies and even American citizens. Let more people in the world understand how the US operates, and how despicable and disgraceful it is.

The US' malpractices in cyberattacks and surveillance are too numerous to count. The various actions of the US are aimed at pushing the world toward "permanent digital hegemony" for the US. The US is the global enemy of cyber security, yet it pretends to be the "guardian" of international cyber security. Its domineering and hypocritical nature has been exposed and condemned by the world.